Using Minecraft as a Therapeutic Tool in Family Therapy

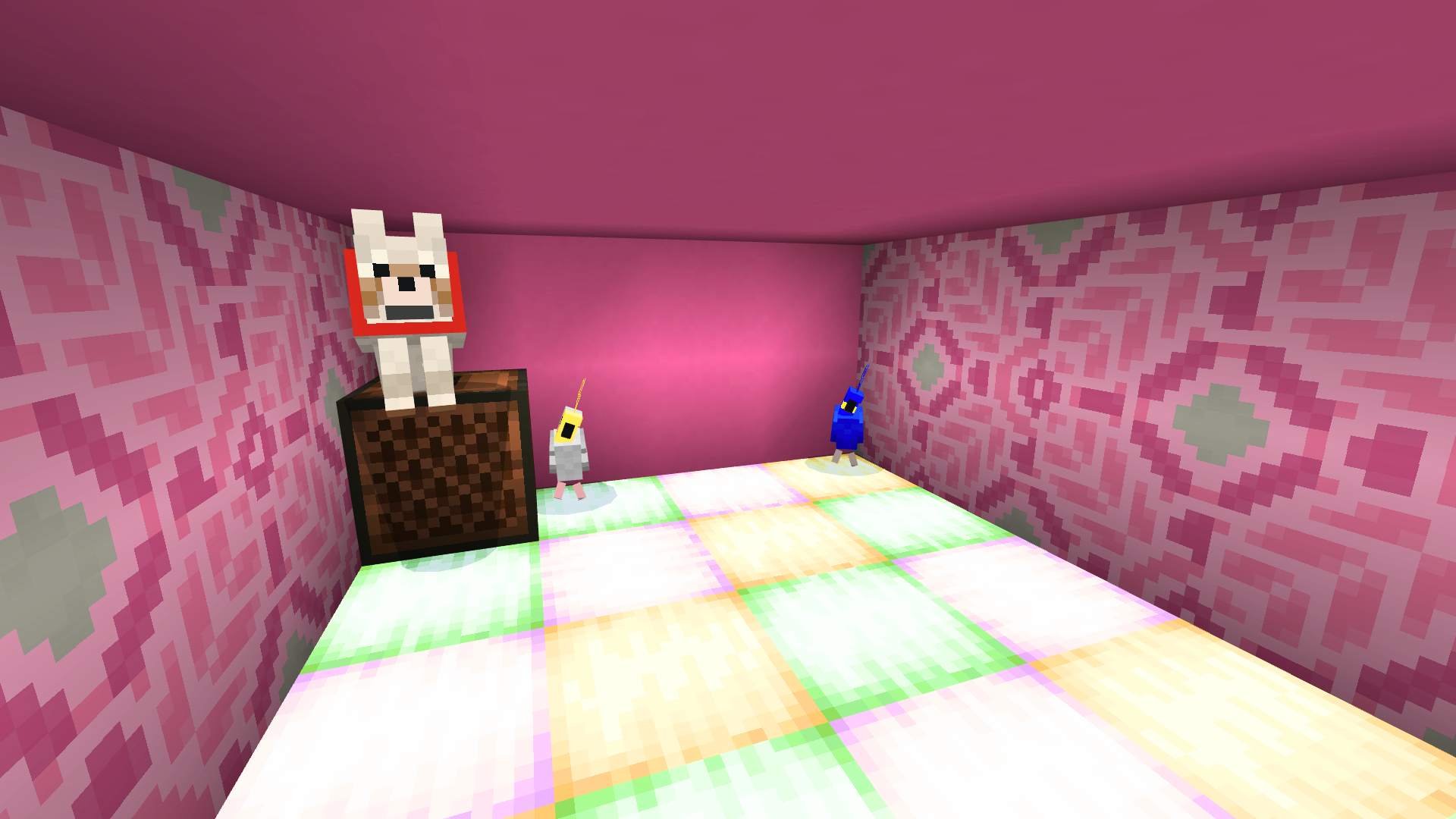

The Bettany family’s totems. James’ totem includes the sea pickle his sister placed to represent him, saying it was ‘because he glows in water’. These symbolic choices prompted affirming and playful conversations.

I’m excited to announce an academic paper I have co-authored with Mark Rivett titled ‘Systemic Therapy Through a Pixelated Lens: Using Minecraft in Therapy With Families That Include Autistic Children and Children With ADHD’ has been published in Wiley’s Journal of Family Therapy.

The article features two families who took part in systemic therapy sessions with me within the popular videogame Minecraft. The sessions took place within my online private practice in the UK.

The article has been a work in progress since summer 2023 and was shaped through several rounds of peer review. We’re grateful to the Journal of Family Therapy editor, Sarah Helps, and to the peer reviewers for their helpful feedback throughout the process.

The article itself only had space for four images. Minecraft, however, is a highly visual medium. In this accompanying blog, I’m therefore sharing some additional images to sit alongside the article and help illustrate the activities and processes that took place during sessions with the two families.

We’re deeply grateful to the two families for their generosity in allowing us to write about their therapy sessions and to share images from their work with the wider therapeutic community. The case material that features in the article and this blog has all been anonymised and run past the families for their approval.

I’ve been very fortunate to have Mark Rivett as my clinical supervisor since 2022. Mark co-authored Family Therapy Skills and Techniques in Action and created a series of accompanying demonstration videos of family therapy sessions. I remember watching these during my training and finding them invaluable. Those videos later inspired the films I co-created as part of the Bridging the ChASM project at the University of Cambridge.

For me, it is really important to share what therapy in Minecraft actually looks like, so practitioners can begin to envisage how this form of digital play in therapy, and other creative digital tools, might be used in their own practice. I hope both the article and this blog help with that. While the techniques described in the article involve directed activities, it is also important to note that Minecraft lends itself well to non-directive therapeutic work.

You can read the full published article for free here:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/share/author/N2IYPMVNSRUA6ZPJYREY?target=10.1111/1467-6427.70020

Part 1 of the article explores the history of videogame therapy, how Minecraft aligns with systemic therapy, existing therapeutic applications of Minecraft, the origins of my own work using Minecraft, and possible reasons why Minecraft is particularly appealing to many neurodivergent people.

Part 2 of the article introduces the families and the systemic therapy work we undertook together in Minecraft. Below is a summary of some sections of Part 2 alongside additional illustrative images. Readers can find further clinical detail in the full published article.

Introducing the families

The Bettany family consisted of two children and their parents. During the work, both children were awaiting diagnoses: ADHD for James (8) and autism for Emma (15), which they received after the sessions ended. Anxiety was a central theme for the family, alongside experiences of distance between siblings and a family history of loss. The focus of the work was on reducing the impact of anxiety within the family system.

The Stevenson family also included two children and their parents. At the time of the work, Robin (10) had recently received diagnoses of autism and ADHD and was experiencing difficulties including anger, anxiety, and self-esteem. The parents were working to support him while also ensuring that his younger sister Lily (7) did not feel excluded and were reflecting on how to work together as parents in this context.

As outlined in the article (Section 2.1), both families were White British and were seen for 10 online systemic therapy sessions within my private practice.

Practical and safety considerations when using Minecraft in therapy

Working therapeutically within Minecraft requires careful attention to practical and safety considerations.

For both families, this included a technical support session before therapy began, alongside consideration of digital competence, privacy, and data security. This involved understanding how Minecraft worlds are stored, how privacy settings function, and how to keep client material secure, as well as supporting families to use the technology safely within online therapy. Minecraft exists in two main commercial editions (Bedrock and Java) and a third (Minecraft Education), widely used in schools and valued by therapists for its additional safety and moderation features.

PlayMode Academy’s training programme in Using Minecraft as a Therapeutic Tool has been developed by myself to support practitioners to integrate Minecraft safely, ethically and effectively into their practice.

Establishing a safe therapeutic space

Systemic work with both families began with establishing a safe therapeutic space. In Minecraft, this was introduced by inviting families to build a ‘safe place’. For readers unfamiliar with Minecraft, this is a familiar in-game activity that mirrors how players often begin play by creating shelter. In therapy, it also provides a concrete starting point for exploring safety, boundaries, closeness, and independence within family relationships.

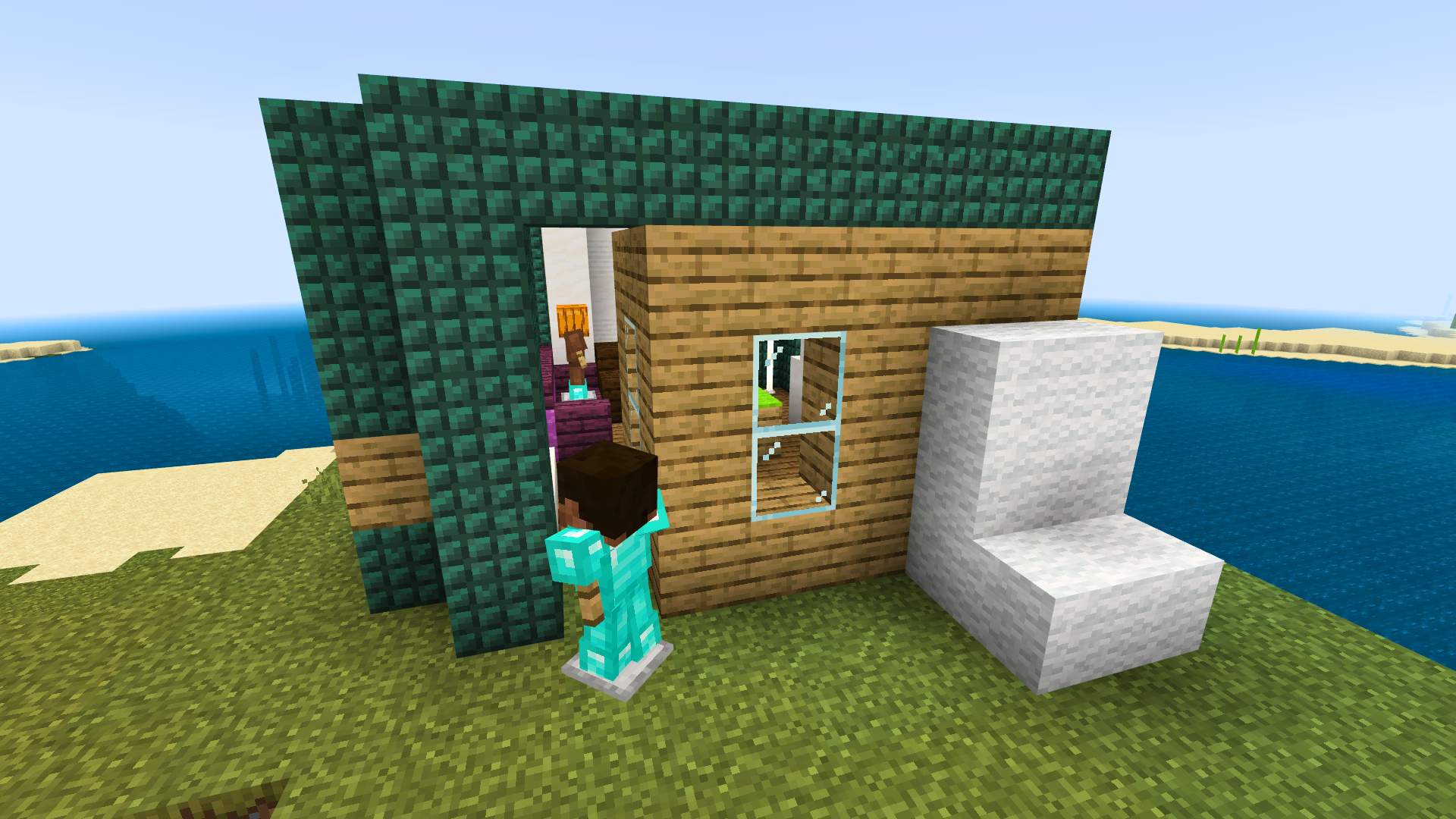

The Bettany family’s safe place

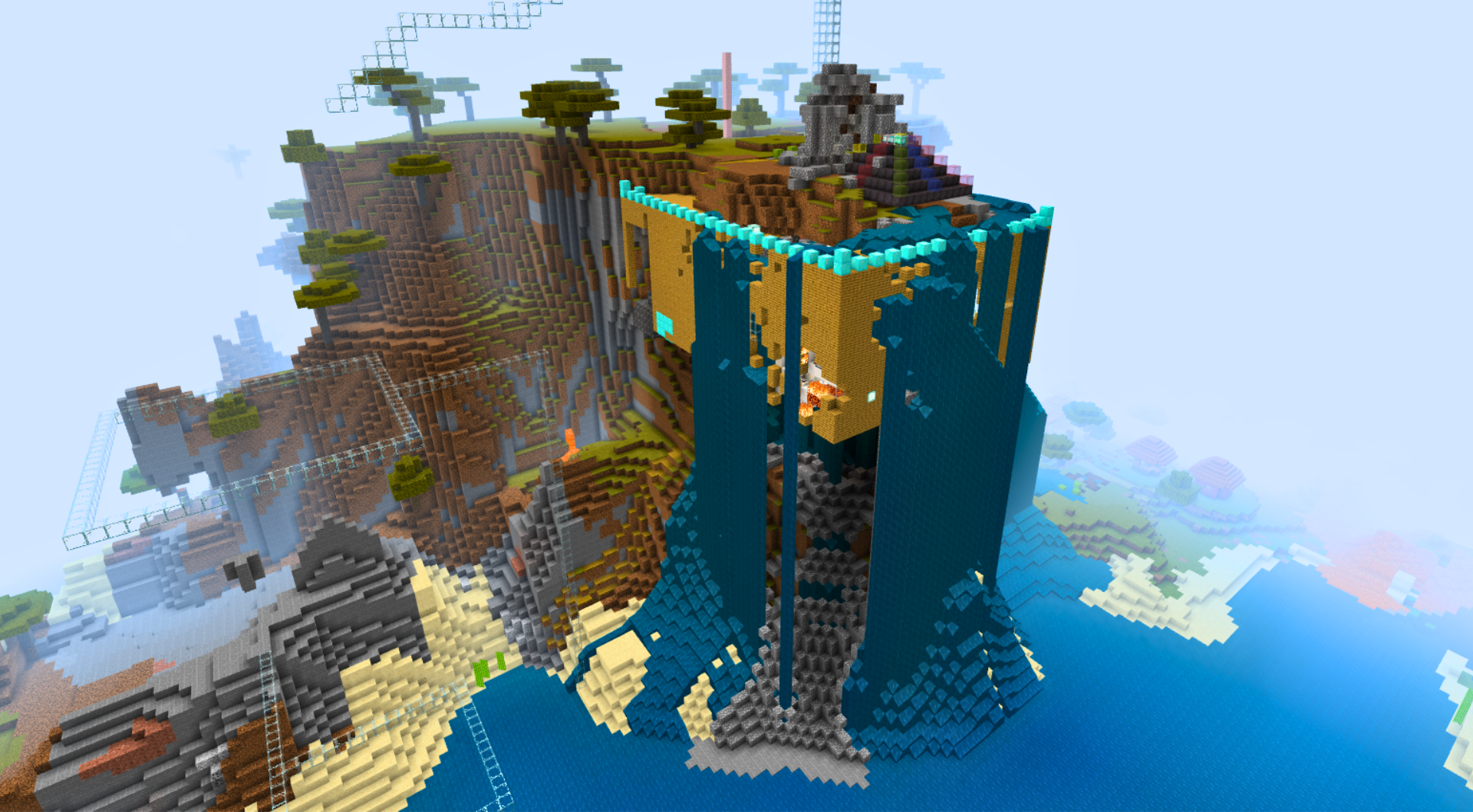

With the Bettany family, the invitation to build a safe place resulted in different family members creating connected but distinct spaces. These included underground and above-ground areas, linked together through shared structures.

‘The mother, less confident with Minecraft, relied on her son to build a house, while Emma created an underground “disco den” accessed via a trapdoor – perhaps reflecting her need for sensory control or adolescent privacy. Her father added a shed above the trapdoor, linking the spaces in an unexpected way.’

Working in this way allowed the family to show, rather than explain, how they experienced togetherness and separation. The resulting builds became reference points for conversations about proximity, independence, and connection within the family system.

The Stevenson family’s safe place

The Stevenson family built their safe place together across two sessions. Each family member contributed differently, including shared construction, hidden passages, and playful additions.

Some of these additions led to moments of tension within the game, such as when changes disrupted what others were building. Importantly, these moments were followed by repair. As explored in the article, this meant that difficulties could be noticed and worked with in real time, rather than avoided.

Assessment: Mapping Family Systems and Relationships

I often use Minecraft as a three-dimensional assessment tool, translating familiar systemic practices such as genograms into digital form.

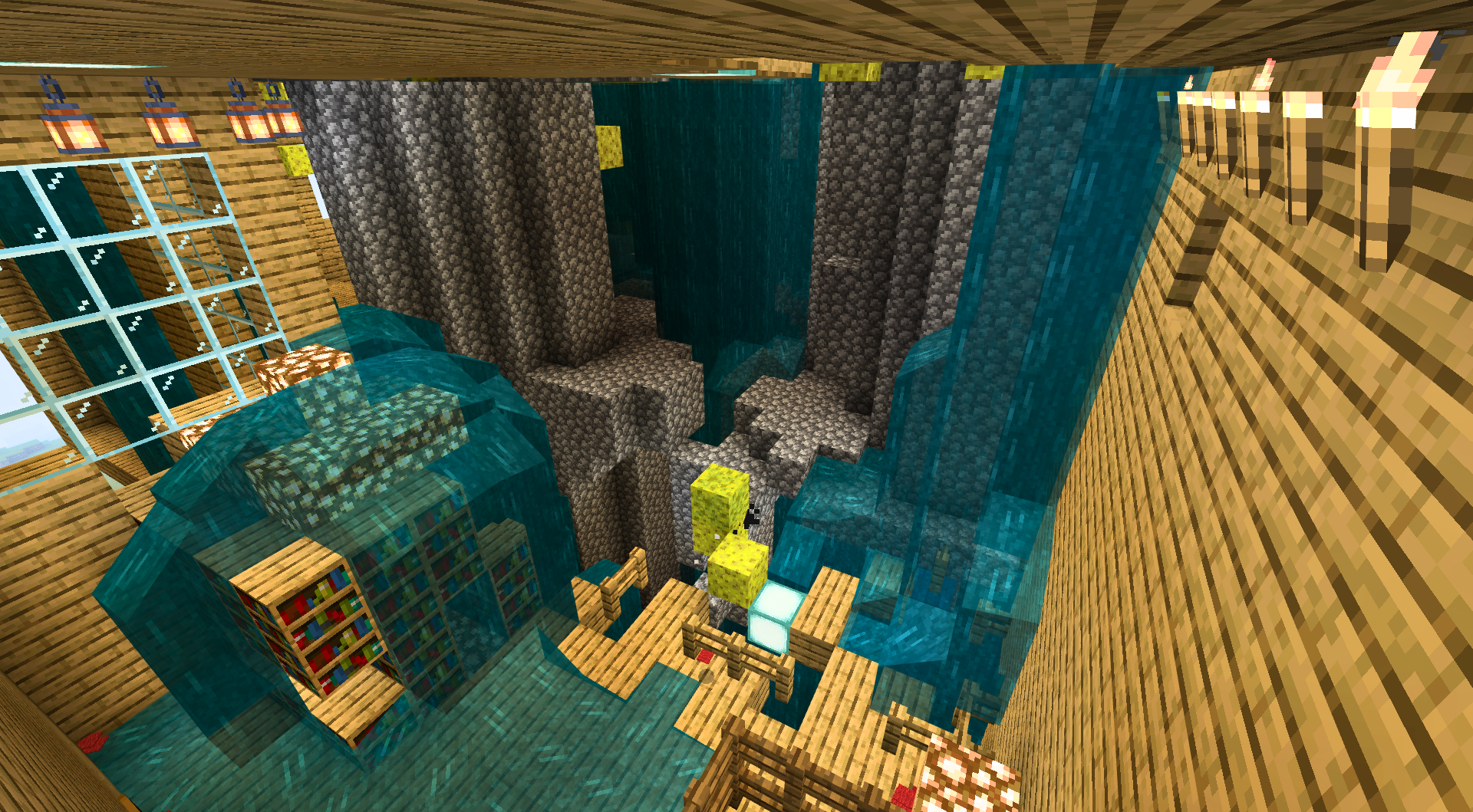

Families were invited to select blocks and items from Minecraft’s inventory to represent themselves and one another, creating symbolic ‘totems’. Each family member chose blocks to represent something positive about themselves and each other, and explained their choices as they built. This offered a visual and relational map of strengths, closeness, and connection, and supported reflective questioning within sessions.

The Bettany family’s totems. James’ totem includes the sea pickle his sister placed to represent him, saying it was ‘because he glows in water’. These symbolic choices prompted affirming and playful conversations.

Externalisation

Externalisation is a well-established systemic and narrative practice that separates people from the problems they are experiencing.

In the work with the Bettany family, anxiety emerged as a shared theme. Externalisation was adapted within Minecraft by inviting the children to create representations of anxiety in the game world.

James created a scene titled Me trying and failing to get rid of anxiety, showing himself alongside a large monster separated by a door. Emma created a contrasting representation, building anxiety as a rift in the earth that all family members might fall into.

Seeing these representations side by side made it possible to explore different experiences of the same difficulty. As discussed in the article, this supported a shift from anxiety being seen as belonging to one child, towards anxiety being understood as something that affected the whole family system.

Circular and Reflexive Questions: Sculpting the Past, Present and Future

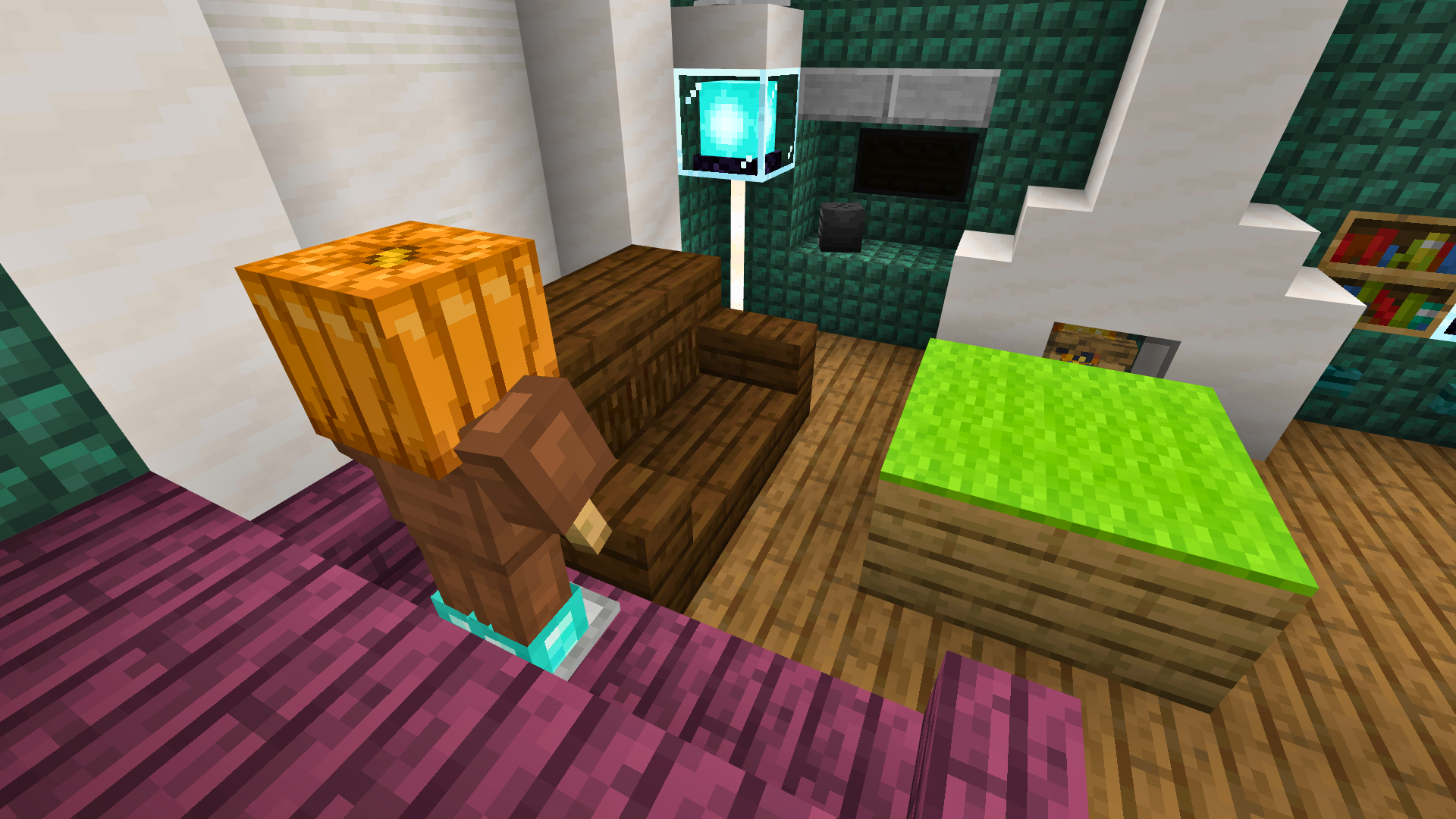

Circular and reflexive questioning was adapted through a past–present–future sculpting activity in Minecraft with the Bettany family.

Using a digital copy-and-paste of the family’s Minecraft living room (created by the family in Minecraft), three versions of the same space were created and labelled past, present, and future. Family members were invited to place representations of themselves within each space, allowing them to explore how relationships had changed over time and how they imagined the future.

This activity made abstract ideas about change visible and concrete, supporting reflection without requiring lengthy verbal explanation.

Past

In the past sculpt, Emma and her father placed themselves outside the living room, while James and his mother sat together inside. Anxiety was represented by a figure with a Creeper head, a Minecraft creature that explodes and causes damage in the game.

Circular questions were used to explore this arrangement, such as who might feel most lonely or most unhappy in this scene.

Present

In the present sculpt, the family again placed themselves apart, but described this as more positive. The father positioned himself moving towards the mother, Emma and James placed themselves together reading, and the mother placed herself alone watching TV, which she described as a way to relax.

Questions explored how being alone could feel different when it was chosen rather than imposed, and how togetherness in the present differed from earlier experiences.

Future

In the future sculpt, each family member created a preferred space representing how they imagined things could be. These included a garden, a BBQ area, a theatre with an applauding audience, and a large figure holding a microphone with a sign reading ‘I’m not anxious’.

Reflexive questions invited the family to consider how others might feel when seeing these future spaces, and what felt most different from the present.

Relational reflexivity

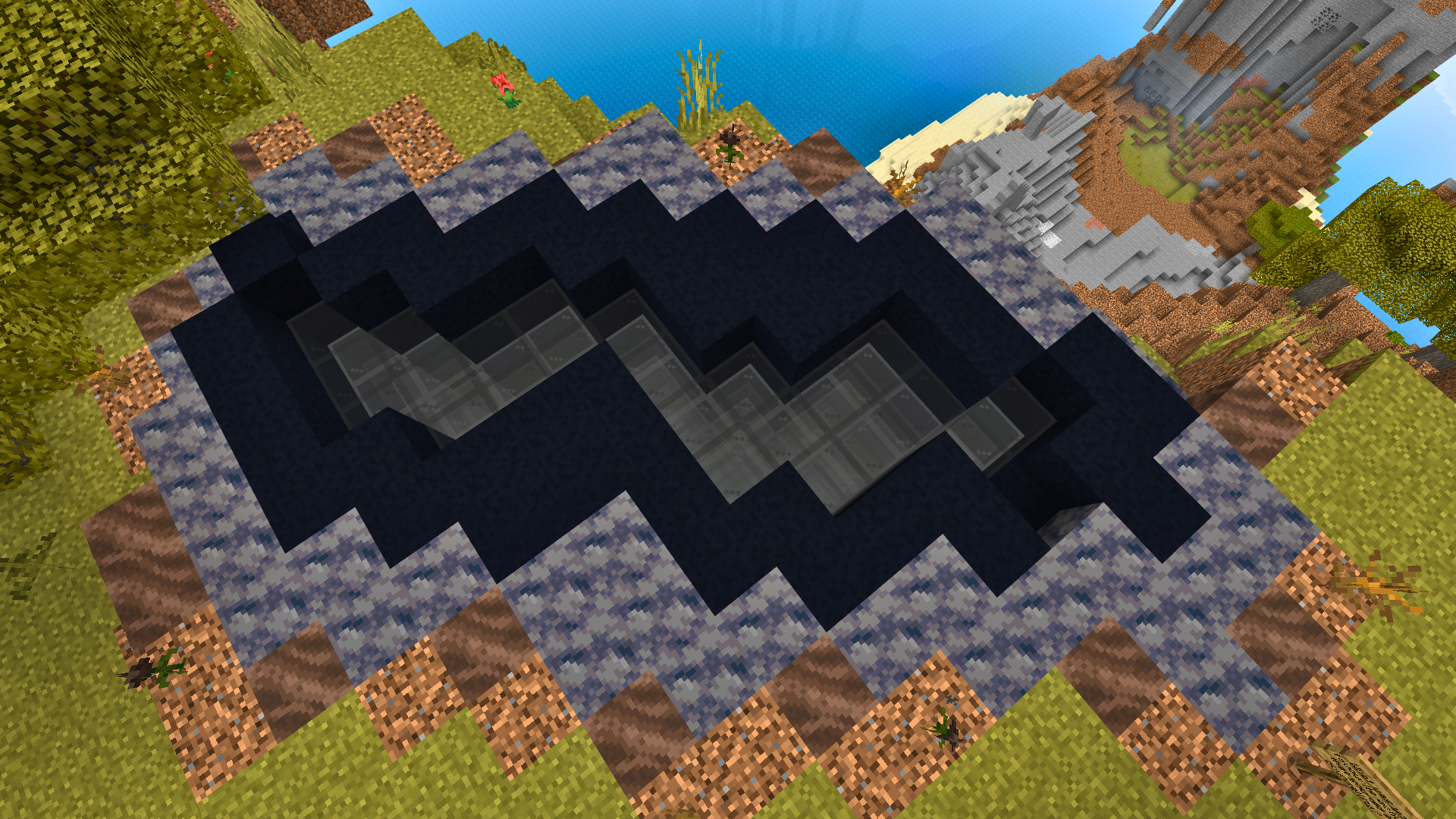

In one session with the Stevenson family, damage occurred to the shared Minecraft safe place. Rather than treating this as a problem to be avoided, the moment became an opportunity for reflection and repair.

The family worked collaboratively to repair the space. In doing so, they likened the process to kintsugi, the Japanese art of repairing broken ceramics by highlighting cracks rather than concealing them. Rather than returning the build to its original form, the family adapted it, filling cracks with windows and adding a rainbow feature wall.

The images below show the space before and after repair, illustrating how rupture and repair became part of the therapeutic process rather than something separate from it.

Reflections on the work across both families

Looking across the work with both families, what stands out to me is how Minecraft functioned as a shared, relational space.

In both cases, the game provided a context where meaning could be co-created through interaction – not only between family members, but with the environment itself. Building, altering, and repairing the world made patterns of closeness, distance, and responsibility visible in ways that were often easier to engage with than abstract conversation.

Minecraft also appeared to redistribute power within sessions. Children were frequently positioned as experts in the game, while adults – including myself – were invited to learn from them. This shift supported moments of shared enjoyment, curiosity, and collaboration, which became important relational resources within the work.

Across the sessions, moments of difficulty or disruption were not treated as failures. Instead, they became opportunities for reflection and repair, illustrating how families could influence patterns together rather than locating problems within one individual.

Why Minecraft can be such a good therapeutic space for neurodivergent children and young people

Many of the patterns visible in the work with the Bettany and Stevenson families reflect broader reasons why Minecraft can be such a supportive therapeutic space for neurodivergent children and young people.

As explored in the article, Minecraft aligns well with the strengths and preferences of many autistic children and children with ADHD.

The game offers a flexible, visually structured environment that supports different ways of engaging – including solitary, parallel, and shared play. It allows for deep focus, creativity, and choice, while reducing pressure around verbal communication and social performance.

Minecraft also supports symbolic expression. Feelings, relationships, and experiences can be represented through blocks, spaces, and movement, enabling communication that does not rely solely on words. For many neurodivergent children, this can make therapy feel more accessible and less demanding.

Perhaps most importantly, Minecraft is already a familiar and meaningful space for many young people. Working within a medium that children know and value positions them as active participants and contributors, supporting agency and engagement in ways that more traditional therapy settings may struggle to achieve.

Curious to learn more?

I’m often asked how practitioners can begin to use Minecraft and other creative digital tools in their own work. My training through PlayMode Academy is shaped directly by practice like that described in this article. I focus on helping practitioners understand not just what to do in Minecraft, but how and why it can support relational work, accessibility, and shared meaning-making. Training is designed to build confidence with both the technology and the therapeutic thinking that sits alongside it, supporting practitioners to integrate creative digital tools in ways that are safe, thoughtful, and responsive to the children and families they work with.

You can find out more about PlayMode Academy’s trainings here.

Feedback from the children

I hope the article and this accompanying blog have been helpful in bringing to life the therapeutic work that is possible within Minecraft. For practitioners interested in videogame therapy, using Minecraft as a therapeutic tool, and creative digital tools in systemic practice, I hope this offers a clear sense of how this work can unfold in real sessions.

I’d like to end this blog with some feedback I received from the two children from the Stevenson family:

“It was fun and enjoyable to spend time with my family in a videogame world where nothing can go wrong or be a failure. It was really nice knowing your family was there with you and sometimes they could help you with a build. It was fun being able to teach Mummy and help her along. It was fun to see all the creative things that Daddy came up with.”

(Lily)“The positive thing was that I like Minecraft. It felt like fun rather than therapy… It was a good space for us to talk about things in. I loved playing Minecraft with Mummy.”

(Robin)

If you have read the article, I’d love to hear your thoughts, so please feel free to get in touch.

The article has been published in Journal of Family Therapy and is available to read for free here: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/share/author/N2IYPMVNSRUA6ZPJYREY?target=10.1111/1467-6427.70020.

Here is the full citation for the article:

Finch, E., and M. Rivett. 2026. “Systemic Therapy Through a Pixelated Lens: Using Minecraft in Therapy With Families That Include Autistic Children and Children With ADHD.” Journal of Family Therapy 48, no. 1: e70020. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.70020.

The images shared in this blog are screenshots taken during real therapy sessions conducted in Minecraft and include therapeutic material created by families. They are shared with explicit permission from the families for use in this blog only. These images must not be copied, downloaded, reproduced, or redistributed in any form.